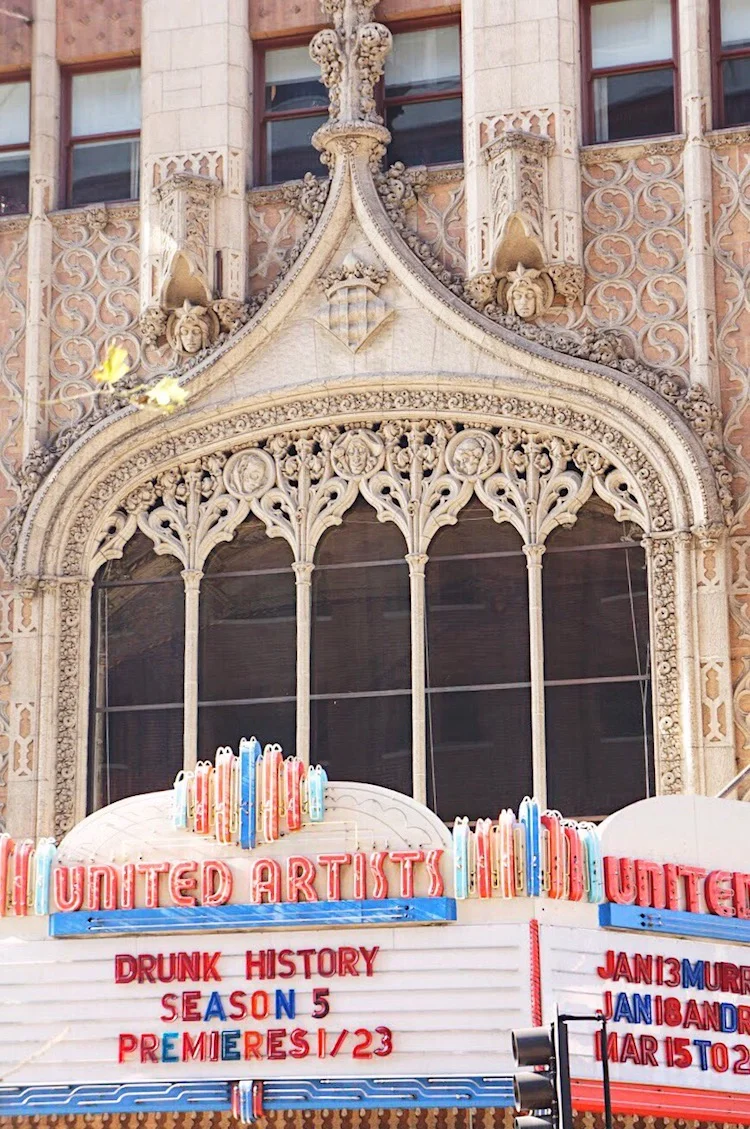

On a Saturday afternoon in 1927, with Douglas Fairbanks beside her, the “girl with the curls” Mary Pickford pulled the lever of a steam shovel and drove the machine’s spade to the ground. A crowd of 5,000 packed Broadway in Downtown Los Angeles, between Ninth and Tenth Streets, to watch the silent film star and entrepreneur do what she did best - put on a show. Pickford excavated the first earth from the site of her soon-to-be-built movie palace, United Artists Theater.

The $3.5 million theater helped define an era and a new building type: the dedicated movie palace. These were grand structures built not to hold vaudeville acts, operas, or plays, but to showcase entertainment’s hottest medium: films. In fact, on December 28, 1927, the day after United Artists Theater’s grand opening, the Los Angeles Times wrote that the theater “gives a new pre-eminence” to movie going. United Artists Theater closed in 1989, having ceased to serve its purpose as a movie house. Around it, Broadway itself had ceased to serve as Los Angeles’ cultural center. United Artists Theater and other large, single-use, single-screen movie theaters became less of a draw, and America’s movie palaces fell into latency, disrepair, or both.

By the 1980s, there had been a massive geographic shift in population to suburban and exurban areas, leaving downtown movie palaces with few patrons. At the same time, given their sheer size and configuration, historic theaters had no other practical use than to show movies. “They are purpose-built for one thing,” says Escott Norton of Friends of the Rialto, a group advocating for the restoration of South Pasadena's historic Rialto Theatre (featured in the Oscar nominated film La La Land). This made historic theaters a uniquely unpopular building choice for preservation, according to Christina Morris, Director of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s L.A. office. More often than not, the theaters ended up as white elephants.

Tower Theater, DTLA

Orpheum THeater, DTLA

With historic movie theaters also came historic technology. Converting to new technology was prohibitively expensive, particularly for independent theater owners and operators. A conservative estimate by Indiewire puts a digital cinema retrofit at $65,000. The Culpeper State Theater in Culpepper, Virginia spent $1 million on a state-of-the-art sound system upgrade as part of their $10 million project. CEO and President of the National Association of Theatre Owners, John Fithian, issued a blunt decree to historic theaters with outdated technology: “Convert or die.” Die many of them did.

Each year since 1988, the National Trust for Historic Preservation releases their “11 Most Endangered Historic Places List.” In 2001, an entire category appeared as an item on the list: “Historic American Movie Theaters, Nationwide.” But since then, the National Trust has named only one historic movie theater to the list (in 2008). Tisha Shelden, Membership Services Coordinator with the League of Historic American Theaters (LHAT), points to an uptick in historic theater restoration in recent years, particularly after the 2008 Great Recession. It’s no coincidence, then, that L.A.’s Bringing Back Broadway initiative launched in 2008. The 10 year plan to re-activate the historic Broadway district (the largest concentration of historic theaters in the nation) was intended to combat ground floor vacancy rates of nearly 25%, notes L.A. City Councilmember Jose Huizar, who led the initiative.

Lobby check in @ Ace Hotel DTLA. The Ace purchased and restored the United Artists Theater, converting a portion of the building into the hotel.

Historic movie theaters have an emotional draw, as “generations of families have memories tied to their local movie house,” notes Escott Norton of Friends of the Rialto. In 2013, Webster City, Iowa was on the brink. “Shut the lights off - we’re done,” recalled resident Jake Pulis in an interview with the Iowa City Press-Citizen. That changed with an effort to preserve the historic Webster Theater, originally built in as a live venue in 1909 and converted to a movie palace in 1939. Webster City residents rallied and raised $200,000 for the preservation effort. The restored theater begot new business nearby and a new lively spirit in a town once thought to be done for.

Oregon-based preservation consultant George Kramer, who led efforts to restore movie theaters in Oregon and Northern California, explains “[historic] theaters create off-hour foot traffic and extend the business day beyond 5 p.m.,” thereby helping to support local restaurants and businesses. In Culpepper, Virginia, a 2013 theater restoration was shortly followed by a nearby $3 million project by a private developer and restaurateur (although this was followed several years later, in September 2016, by news that Culpepper was going dark due to financial constraints). In Medford, Oregon, the Holly Theater (currently undergoing restoration) is expected to add $3 million to the local economy annually, according to the Holly Theater’s website.

Los Angeles Theater, DTLA

Palace Theater, DTLA

The economic benefits of historic movie theater preservation are important, but they are by no means automatic. The success of these projects is not solely a factor of the physical preservation. “You can only go to a historic theater twice to soak up the plaster,'' observed a 1981 New York Times article about historic theater restoration. It is a fact that remains as true today as it was over 35 years ago. Rather, success hinges on continuous and smart programming designed for the space. That is why these movie palaces are being reborn not necessarily as movie theaters, but as live entertainment venues and arts and community spaces. “It's about finding new ways to keep buildings vital in the future. This means enlivening the theaters with uses and programming as often as possible,” Councilman Huizar says.

For L.A.’s Broadway, smart programming that attracts large and diverse crowds is a result of a curatorial approach: juxtaposing historic architecture with modern performances and culture. It makes theaters more dynamic, both economically and culturally. This kind of programming creates multiple sources of revenue for the theater. “That means individuals can find investors willing to take on the risk [of preservation],” says Tisha Shelden of LHAT. Key investment helps supplement the federal, state, and local grants and tax credits that typically make these kinds of historic preservation projects possible. Culturally speaking, showcasing a more varied and higher volume of programming enables theaters to cater to the changing tastes of their communities.

Los Angeles' historic Broadway district has the largest concentration of historic theaters in the nation.

The former United Artists Theater, for example, reopened in 2015 as the Theater At The Ace Hotel. In a 2016 interview with the Los Angeles Business Journal, Kelly Sawdon, Partner and Chief Brand Officer at the Ace, explains that hosting live events marries “really well with what we wanted to do with the theater – using it in lots of different ways to help support the creative cultures in the city.” A dynamic range of events has enabled the theater to fill its calendar virtually every other day of the year. While the theater occasionally shows films, it also hosts special performances by the L.A. Opera, concerts, live podcasts, stand-up comedy, ballet and other dance performances, and more.

Best Girl Restaurant, now a part of the united Artists Theater's building

The Egyptian Theater in Coos Bay, Oregon, built in 1925, shuttered in 2011. It reopened in 2014 and now hosts community celebrations, concerts, and fundraisers, in addition to showing films. The Holly Theater in Medford, Oregon, built in 1930, closed its doors in 1986. It plans to offer an array of concerts, comedians, sing alongs, and live theater when it reopens to “drive [...] a vibrant community.” In Northern California, Redding’s 1935 Cascade Theater was once a cinematic haven in which to escape Depression-era struggles. Restored in 2004, it is now a multi-use performing arts center.

Live events require more participation from their audience than films. They evoke a shared sense of interest and community for a population eager to live a more experiential lifestyle. “[Movie theaters] build community from the time their restoration is announced,” says preservation consultant George Kramer. Civic engagement drives economic activity. That is why maintaining and growing that sense of community is integral to the success of restored historic theaters.

At the same time that appeal for historic movie theater preservation projects had risen, social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram have emerged as instruments for Millennials to curate picture-perfect virtual lives. For Millennials, attending once-in-a-lifetime type experiences are the key to curating that life. A 2014 study by Harris Group and Eventbrite found that the “fear of missing out” (FOMO) on these experiences and the desire for validation through “likes” drives purchasing decisions towards more experiential purchases. To that point, the study also found that more than 8 in 10 millennials (82%) attended or participated in live experiences over the course of the year.

Desire for validation through “likes” drives Millennials' purchasing decisions towards more experiential purchases.

Palace Theater, DTLA

With Millennials’ estimated combined spending power at $200 billion annually it is smart business for recently restored historic movie theaters to make a programming change. Another key finding from the study says that experiences such as these help shape identity by creating lifelong memories. With live event programming historic movie palaces are helping shape identities therefore ingraining themselves deeper within their communities. It is a move that ensures their longevity beyond their own opening weekend.

Restorations of historic movie palaces increased following the 2008 Great Recession. But a new administration in the White House appears intent on slashing arts and cultural funding from the federal budget, and is development-friendly, building regulation-averse, and has re-written the tax code rendering historic tax credits less desirable to developers. It’s unclear whether the trend-line towards restoration will continue or whether the peak has come and gone. Will historic movie palaces once reborn again become a thing of the past?

Ace Hotel DTLA opened in the United Artists Theater building

In Los Angeles, a crowd will once again amass on Broadway, between Ninth and Tenth streets (and also Ninth and First streets) on a Saturday. Mary Pickford’s former United Artists Theater and its brethren are again a beacon of civic engagement. January 27, 2018 marks the fourth annual Night on Broadway, L.A.’s free arts and music festival hosted along Broadway and inside its historic theaters, arcades, and storefronts. The festival, a culmination of the 10-year Bringing Back Broadway initiative, has swelled from 35,000 attendees in 2015 to a crowd of 75,000 at last year's event in 2017.

“It’s great seeing people from all over L.A. come together to bring awareness to these historic theaters by spreading positivity through live art. The beer is great too,” quips 2017 first-time festival attendee Erica Guimarães. Interactive art exhibitions, concerts, and live acrobatic performances present a grand juxtaposition of the historic and modern. Under an awning of ornate columns and lavishly scalloped archways, and in a halo of neon, a line of food trucks dish up the latest in street fare 90 years after Mary Pickford’s steam shovel broke ground.

// All photography by Marni Epstein-Mervis of STRUKTR Studios